On 4-5 October 2013, The New School`s Historical Studies Department convened various scholars, activists, and artists to address critical questions about history and contemporary politics in Turkey under the rubric of the Talk Turkey Conference: Rethinking Life Since Gezi.

One of the panels of the conerence was entitled "Rethinking Gezi through Feminist and LGBT Perspectives," and featured presentations by Cihan Tekay (Co-Editor of Jadaliyya`s Turkey Page), Zeuno Ustun (Graduate Student at the New School), Bade Okçuoğlu (Bosphorus University), and Sebahat Tuncel (Turkish MP). Below is a video of the panel, followed by transcripts of the panel`s presentations.

Panel Video

Panel Transcripts

[Note: It was not possible to obtain Sebahat Tuncel`s presentation in written formatt]

"A Short History of Feminism in Turkey and Feminist Resistance in Gezi" (By Cihan Tekay & Zeyno Ustun)

Part I: History of the Woman Question and Feminism in Turkey

Republican Period

In the Turkish case of nation-building, women have been instrumentalized to define modernity. The image of the new “modern” Turkish woman was directly controlled by the state policies of the Republican era, which facilitated the cultural revolution deemed “necessary” to build the new independent, modern, Westernized, and secular Turkish nation. The modernization project not only marked the modernization of institutions, but prescribed the modernization of the “social imaginary” and of everyday life through gender.

The reforms implemented for women in 1920s Turkey were born out of the politics of the single-party era, which viewed women`s rights as a requirement for the formation of a democratic nation-state. Decision-making for the new Turkish nation in the new “democratic” environment of the new state was also heavily gendered by a legacy of patriarchy and male-domination, supplemented by exclusionary policies that were directed to women`s movements. When women’s political parties sought to participate in the political realm in the Early Republican Period, it was argued that the republic had given women all their rights and there was no more need for women to organize.

Dress lay at the center of the understanding that all forms of life, even private life, should be similar to the social life of the West. These new forms were introduced as the essential symbols of modernity, and had to be followed if one was to access the public sphere and to benefit from the state`s facilities. The veil or the headscarf was directly associated with “tradition,” and thus deemed “uncivilized,” considered to be getting in the way of Turkey`s efforts to join the realm of the “civilized” nations.

The first ban on veiling was implemented through the Ministry of Education as early as 1924. The issue of women`s veiling in institutions of higher education remained an issue throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, as women in Turkey protested the denial of access to universities since the 1980s, in the aftermath of regulations set by the Higher Education Committee (YÖK), and the debate on this issue has became a national concern that has been taken up repeatedly in the national assembly. The recent “democratic package” lifts the ban on the veil in public institutions, except for the police and military establishments.

Kemalist egalitarianism, while encouraging women’s equal participation in the public sphere, also conceived of women primarily as mothers and wives. Therefore, women’s access to education was framed in these terms. The expectations from women to fulfill their duties to the nation through motherhood and through the preservation of their unpaid labor in the household, while simultaneously entering the workforce, created a gap between women`s perceived and lived realities.

The construction of the “new” women who are successful both in their careers and in being good housewives and mothers conceals the emergence of a class of female servants to alleviate the burden of housework for the upper-class professional women. This untold history of female labor created a dividing line between upper-class professional women who joined the workforce in the public sphere and the working-class women who remained in the private sphere by providing domestic labor in upper-class households.

1980s - Present

If the roots of the woman question in modern Turkey can be found in the Republican era, the awakening of feminist consciousness can be traced to the 1980s. In the 1970s, feminism was defined in Turkey within the Marxist framework, as Marxism was the dominant paradigm of the left in Turkey, as embodied in the student and worker mobilizations of the decade. After the 1980 coup, which marked the onset of neoliberalization in Turkey and instituted a major crackdown on the radical left, leftist women regrouped and started feminist discussion groups in private homes, as political repression continued during the first five years of the decade, limiting public political activity. “Personal is political” became a part of these women’s lexicon, as they experimented with non-hierarchical meeting structures. The meetings were followed by street actions in the latter part of the decade, such as marches against domestic violence, and a successful campaign for the annulment of the infamous Article 438 in the Turkish Penal Code, which considered female rape victims “whores.”

In the 1990s, the feminist circles grew from a minority of women who mostly came out of the 1970s Marxist left to include Kemalist as well as Muslim women. Simultaneously, feminist and women`s initiatives were institutionalized as NGOs, women`s journals, collectives, and task forces within trade organizations. Attempts to bridge the distance between Turkish feminists in the West and Kurdish women`s struggles in the east were initiated, especially under the banner of campaigns against domestic violence and other violence against women. Simultaneously, a rapprochement between secular feminists and their Muslim counterparts started growing, as they collectively protested women`s right to access education and public space, as veiled women were denied entry to universities through the provisions of the Higher Council of Education.

The 2000s saw many gains for the feminist and women’s movements, as many reforms were passed on the parliamentary level. The Civil Code was revised to end the patriarchal hegemony of the husband in the family on the legislative level; the Penal Code was rid of many articles that disproportionately disadvantaged women. Laws were passed to protect women from domestic violence, and constitutional reforms acknowledged the need for the state to institute affirmative action.

Another important development throughout the 1990s and 2000s was the rise of an autonomous women’s movement within the Kurdish movement. Kurdish women started to play important roles within the Kurdish political parties and organizations, actively confronting and challenging the patriarchal structures of these political formations. They influenced the charters and regulations of the consecutive Kurdish parties, implementing gender quotas and gender-balanced co-chairpersonship structures, which ensured the consistently high participation of women in politics.

Beyond self-defined “feminist” or “women’s” movements, Saturday Mothers and Peace Mothers became emblematic of the 1990s and 2000s in Turkey. The military coup of 1980 and the Turkish state’s brutal policies in Kurdistan resulted in massive political repression of young people who struggled within left and Kurdish movements. Mothers became politicized actors in the public sphere as their children were “disappeared” in these decades, unrecorded victims to military, police, and paramilitary forces.

Before Gezi

Although we cannot exhaust all the developments pertaining to women’s struggle within the last decade, we want to touch on some major developments that occurred before the Gezi uprising took place. We have previously established that feminist struggle in Turkey predates the Gezi uprising. Now we will explore how the struggle has intensified during the conservative and neoliberal AKP rule. During this period, policies have been implemented that directly seek control over the female body, reducing it to a site of biological and labor reproduction. With these policies, the female subject has been denied the space to exist with all her complexities, reduced to a monolithic passive entity of patriarchal political hegemony.

The major issues that occupied feminists in the last few years before Gezi were domestic violence and femicide, the AKP’s policies of population control through control of the female body and reproduction, and women’s labor under a neoliberal regime. The last few years saw the onset of the AKP’s new population politics, constituting a set of heavy-handed interventions in policies that seek to regulate fertility. A ban on abortion was introduced as draft legislation in 2012, which met with quite a bit of resistance from women, inciting street protests and online activism. However, the virtual ban on abortion is only one segment of the AKP’s policies towards increasing the population, as the government had already been giving out incentives to families with three or more children. The new “package,” a set of bills that are aimed at encouraging working women to give birth by extending the flexibility of work for women during the first few years following pregnancy, has received much criticism from feminists for consolidating neoliberalism’s effects on women’s labor, while also implementing a nationalist agenda bent on increasing the population and reducing women to their role in the family as mothers and wives. Prime Minister Erdoğan’s discourse around abortion and caesarean sections especially aggravated large sections of women, as he compared abortion to the recent Uludere/Roboski massacre in which Kurdish civilians, most of them children, were killed by the Turkish military while smuggling commodities from the border, the only source of income for many families living in border towns where the effects of the thirty-year-long war are deeply felt.

The neoliberalization of the Turkish economy brought about new ways to exploit all forms of women’s labor, an area feminists have focused on in the last decades. Major headway was made during the 2000s, as an all-women strike in Antalya Free Trade Zone, which won at the end of a sixteen-month struggle, influenced a wave of women’s strikes all over the country. It culminated in the Turkish Airlines (THY) labor dispute, beginning with an indefinite action by workers in May 2012, followed by an all-out strike in May 2013, immediately before the onset of the Gezi uprising. Like many other majority-women strikes, the THY strike not only focused on wages but also made demands specifically pertaining to women’s bodies. A ban on red lipstick and hair buns for flight attendants, instituted in April of this year, was the cherry on top of a cake, as attendants had been filing complaints on the long hours affecting their bodies and resulting in chronic illnesses, most of them ironically affecting their reproductive system. The THY strike is important in the context of the new women’s employment package, as it makes clear the government’s vested interest is not in protecting women workers from the violations of capital, but in creating the conditions in which her body is primarily understood as the site of reproduction, and her labor is relegated to partial and flexible participation in the workforce.

In the light of the historical background I tried to sketch here, Zeyno will follow with an analysis of the governmental discourse on women’s bodies and the counter-power response to it from the ground.

Part II: A Timeline of Events on the Ground and Governmental Discourse

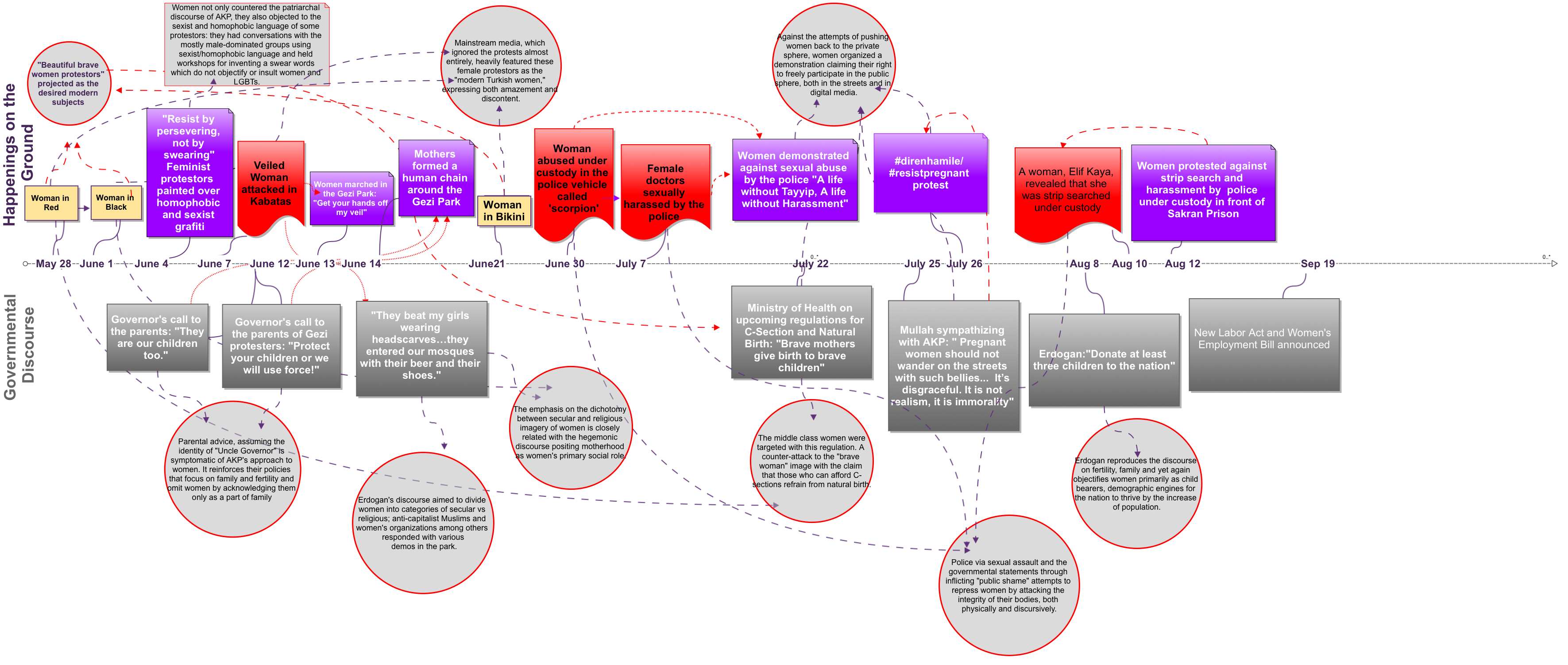

As you can see in the timeline we prepared, we read the happenings in the Gezi Resistance and the government discourse in parallel, in order to understand the flow of both constructive and deconstructive maneuvers of feminist resistance and the government.

There is, however, one more dimension in accordance with the feminist struggle within the resistance. There were patriarchal elements used by the male-dominant groups of protestors as well, which later resulted in encounters between female and male groups of Gezi.

“Let’s see you use that pepper spray. Take off your helmets, drop your batons and let’s see who’s the real man.”

Considering these internal conflicts within the Gezi resistance as well, I want to start with the two female images, which during the Gezi protests became the symbols of the movements. Both the protestors and the mainstream media were amazed by these symbols, while simultaneously failing to attribute any other meaning than symbolic to their active participation.

Both of these figures, the female idols of the Gezi Resistance, Woman in Red and Woman in Black, were promoted as “brave, beautiful women” and projected as the desired modern subjects of the nation. The contribution of these female figures to the increasing numbers of protesters was indeed very important. However, this fascination also points to a patriarchal approach, reproducing the discourse which dwells upon fear, highlighting the fragile and beautiful female body, and even reminding us of the good old republican mythology of women and their courage during the war years.

To illustrate the attention they received, I am going to turn to Google Trends. When you google the keywords Gezi and Kadın, the majority of the links would direct you to stories about one of these women. In fact, as the third event marked with yellow in the timeline, in google trends analysis, the top story was the woman protesting in her bikini in Taksim square and also her being an “immoral atheist woman.”

Nonetheless, the real beauty of feminist politics in Turkey reveals itself not through the resisting female bodies that fascinated everyone, but through the encounters those feminist collectives had with other groups occupying the park. Their workshops, and then painting over the homophobic and sexist swear words with purple, are the strongest and most popular example of this.

The title of the conference today provides a framework, stating a question about what happened since Gezi, but as Cihan already explained, feminists were active political actors prior to Gezi, and they proved themselves to be experienced campaign developers during the Gezi resistance. They were very successful in reconstructing the discourse of the resistance. Therefore, I want to salute the women who did a wonderful job sustaining a counter-language to the patriarchal discourse of both other protestors and the government.

If we get back to what happened on the ground, after Gezi Park remained occupied for a while, Hüseyin Avni Mutlu, the governor of Istanbul, calling himself “Uncle Governor” and giving parental advice, made a call to mothers to protect their children, to whom he also associated himself having paternal feelings. He was basically speaking to the mothers of the protesters, both declaring the youth protesting to be delinquent children and again evoking motherhood as the sole responsibility of women. In his speeches, again the same discursive tones were quite clearly there. He sees women primarily as part of family, addressing them in regard to their motherly protective feelings, which should overrule every other social role, if there is any, for women.

As a response to the governor, mothers went out to the streets, and before the day that police evicted protesters from the park on 14 June, they formed a human chain around the park. They were resisting the police violence hand-in-hand with their delinquent children.

As you can see in the timeline, Erdoğan at the same time was also talking about women’s issues in Turkey from another angle, mentioning the attack on a veiled woman that took place in Kabatas and combining it with how immoral the protests are.

In his exact words: “They beat my girls wearing headscarves, they entered our mosques with their beer and their shoes."

Erdoğan’s discourse aimed to divide women into categories of secular versus religious, which is indeed not something new. But women were rioting together, and this time it was another context. Consequent to his negating discourse, feminists and anti-capitalist Muslims responded with various demonstrations in Gezi Park, disregarding his efforts of segregating the feminist resistance.

Additionally, note that the emphasis on the dichotomy between secular and religious imagery of women is closely related with the hegemonic discourse positing motherhood as women`s primary social role. Women marched on the streets, chanting: “Take your hands off my body, my identity, my veil!”

Then, on 15 June, police brutally attacked Gezi Park after sixteen days of occupation and evicted people from the park. On 16 June, police formed a barricade around the park. Protesters tried to reclaim the ground and Taksim Square. However, police brutality intensified, and they arrested a significant number of protesters, including many women.

The Gezi occupation was over, but the Gezi resistance was being transferred to parks in each neighborhood. Maçka and Yoğurtçu were becoming hubs for feminist groups to assemble and to get organized. Later on, feminist resistance continued, with forums and workshops held every week on various issues of women’s struggle in Yoğurtçu.

On 30 June, a woman revealed her story of being sexually harassed under custody in a police vehicle called a “scorpion.” Overcoming fear and the public shame with the strength they gained through the experience of solidarity, more women started publicly exposing the abuse by the police. After almost a week, the TTB (Turkish Medical Association) posted a declaration on their website about female doctors being sexually assaulted by the police while they were trying to treat the wounded protesters as volunteers.

Right after that on 22 July, women demonstrated in massive numbers, chanting: “A life without Tayyip, a life without harassment”

The police, by violating the bodily integrity of women, and the government, through statements inflicting “public shame,” aimed at repressing female protesters both physically and discursively.

On the day of wide-ranging protests against sexual harassment and violence, on 22 July, the Ministry of Health hinted at the upcoming regulations regarding caesarean sections and natural birth, saying: “Brave mothers give birth to brave children.” The middle-class women, who were mostly the ones marching in the streets, were targeted by this statement. As a discursive move, it was referring to the imagery of “brave women,” contrasting it with the hegemonic discourse on motherhood.

Only three days later, on 25 July on TRT, the state television channel in Turkey, a mullah sympathizing with the AKP stated: “Pregnant women should not wander on the streets with such bellies…It’s disgraceful. It is not realism, it is immorality.” Feminist resistance responded both by marching on the streets and by starting a digital resistance via the hashtags #direnhamile and #resistpregnant on the following day.

Of course, the most piercing maneuver was against the direct invasion of the bodily integrity of women by applications such as strip searches. On 8 August, a woman named Elif Kaya spoke courageously about her experience of abuse under custody, and soon after, a video showing almost a dozen police women forcing her to undress and searching her was released. That was also the case with Yapici and some other female members of Taksim Solidarity when they were taken into custody. Unfortunately, the ones we know of are only the tip of the iceberg.

To conclude, it is an obvious yet to-the-point argument that the AKP government systematically reproduces the subject position of women as they are reduced to child bearers and to secondary or cheap labor forces, through repeating statements about the female body and motherhood, through sexual harassment, and through constant reinforcement of the good old “divide” between the traditional and modern images of women. This is why Erdoğan campaigns for women to donate at least three children to the nation, and that’s why police freely strip search female protestors, and that’s why that ministries come together and develop a bill, heavily criticized by feminists, that makes sure women can be reproduced as mothers and wives and also remain as minor contributors to the economy within the neoliberal and patriarchal projection of the AKP government.

"The LGBT Block" (By Bade Okçuoğlu)

First of all, I want to thank everyone who has participated in organizing this event. I believe such an event makes it possible for us to think further about what happened during the Gezi uprisings.

Secondly, I want to dedicate this talk to our beloved comrade and friend, who has recently passed away, Ali Arıkan. As a trans feminist, LGBTQI rights activist and a self-proclaimed trans man, Ali has contributed quite a lot to the movement here. It wouldn’t be enough to mention here how much we are grateful to him.

So let me start briefly with what has happened at the beginning of the Gezi uprisings and how the LGBT Block has formed accordingly with the events that took place.

The Taksim-Gezi resistance took off in Gezi Park and quickly spread to at least eighty cities throughout Turkey during June 2013. It has already become a milestone in Turkish political history, with the park as its monument. Gezi Park, a physical space in the downtown of İstanbul, soon transcended its physical boundaries. It became a space of freedom, recognition, respect, acquaintance, and embrace.

The LGBT Block has been among the most visible constituents of the resistance. LGBTQ individuals who mostly live in İstanbul formed it. But not all of them were familiar with each other until these events began.

During the first days of the resistance, a spontaneously-hung rainbow flag on one of the trees in Gezi Park became our mark to find each other in the crowd, and it initiated the formation of LGBT Block.

Towards the end of the first week, when police retreated from Taksim Square and Gezi Park, the occupation of Gezi became much more established and organized. As the LGBT Block, we settled down at a central corner of the park, under a banner bearing our name.

For the following two weeks, until the police came back to “clean us out” from the park, the LGBT Block was present in the occupation to provide for a full fledged infirmary service, as well as to distribute free food and beverages twenty-four hours a day.

Groups of volunteers, including random and newly met people who gathered around the LGBT Block banner, organized film screenings and mini marches across the park and helped out with the flyering for the forthcoming Pride week.

These means were essential for us to maintain LGBTQ visibility in the daily life at the park, and such attempts opened up the ways in which new acquaintances became possible.

LGBTQ individuals, who flooded over the streets and barricades, were bearing the memories of their prior presences in public space.

This holds true especially for our trans friends, who are the most recognizable and whose visibility in public space doesn’t come with nice experiences at all. Their memories are “bejeweled” with non-recognition, denial, hatred, and murder.

Within the uncanny affection of such memories, our trans activist friend Şevval told us about her experience during a teargas bombardment. She was able to submit her body daringly to the intense crowd.

She tells what a unique experience for a trans woman like her it was, to run in İstiklal Avenue with her eyes closed, under the teargas. Some people she didn’t know took her arm in the chaos and helped her to get through the gas.

The reason Şevval calls this experience “one of the most interesting experiences in her life” is because such a moment, which is touched with affects of recognition and reliance, contravenes the general themes of collective memories of trans individuals in Turkey: the themes of insecurity, of misrecognition or of not being recognized at all.

From such a point of view, the experience of the Gezi resistance may have made a transformative contribution to the collective memory of LGBTQ people in Turkey. It may have opened up the possibility of thinking what was previously “unthinkable.”

As it had been so for Turkish political history, the Gezi resistance has also become a touchstone in the LGBTQ movement, from its very early days. In the public declaration of the Trans Pride March that took place at the end of June, those days were recalled as a belated embrace that eventually happened for the first time in Turkey.

Simultaneously with the embrace taking place in the space of Gezi, we were getting the unfortunate news about recent hate crimes against our trans friends. They were being exposed to verbal and physical violence during the days of the uprising, particularly outside the space of the resistance.

Unfortunately, these incidents weren’t surprising to us at all, but they may be interpreted in accordance with the effect that the LGBT Block created in and outside of the space of the resistance.

Gezi draws a spatial but not a temporal line between the narratives of recognition and hatred. On one side, there is the account of Şevval, about her submission of herself to the crowd with her eyes closed; on the other side, there is the bad news about Sema, one of our trans activist friends, being attacked in her own neighborhood that is walking distance from Taksim Square.

What this simultaneity points at is I think the following:

The space of Gezi that shattered the narratives of violence surrounding us was actually a space where new relationalities and therefore new meanings could be produced.

As one of our friends, Sedef, mentions in one of her interviews, LGBTQ individuals who participated in the resistance could reach people and make them understand that we are not three eared, five eyed weirdos or freaks. It was a crucial acquisition for us within a time of three weeks, she says.

Due to the communitarian structure of Gezi, LGBTQ individuals were “recognized” as active founding subjects of the space, instead of as the abject members of society.

Many LGBTQ friends reported that before these events began, they wanted to leave this country as soon as they could, but now “for the first time,” they felt at “home” and they weren’t considering leaving Turkey any longer, not particularly at that point.

Another impact of this “feeling at home” was the flourishing of “coming out stories,” which were frequently told during the meetings in which we shared our experiences regarding the process.

Some of our friends told us that, out of the strength and exuberance this process gave them, they came out to their parents as LGBTs. They were saying that Gezi has become their home and its residents became their folk, with whom they were in solidarity, well beyond classes or identities...

Therefore, a friend who came out to his parents during this process was telling us how he cares not a single bit if his parents denied him from that moment on.

There is another side of the story that I would like to stress a bit here. Until this point, I tried to give a brief account of the overwhelming themes in the experiences of people who have participated in the LGBT Block.

Now let me mention some feedback loops that sprang from the space of resistance to the public spaces of mainstream newspapers and television channels, and also to social media, especially Twitter and Facebook.

In the period following the first encounters and reactions, the LGBT Block was mentioned via different channels of media as one of the most favorable groups in Gezi. LGBTQ people were called “heroic” and “as delikanlı as the others” (which means something like “tough guy” in Turkish).

Likewise, in some of the narratives of people who don’t identify as LGBTQ and who weren’t acquainted with us before Gezi, there is a manner of apology in their tone of voice, because of their previous transphobic and homophobic attitudes towards LGBTQ people.

A very similar manner of apology was also seen towards Kurdish people and the Kurdish struggle, after witnessing the manipulation of reality by the mainstream media.

A participant of a large soccer fan organization, Çarşı, told one of our trans friends that he used to swear at prostitutes and transvestites before, but now he will never do that again, since he came to know them and they were able to touch each other.

To recognize and to touch each other; to get acquainted and to embrace each other...

The narratives of these experiences do materialize within the perspective of power; however, once they start circulating around, one may say that they no longer fit into their molds again.

As they circulate, there opens up a space where new meanings, connotations, experiences, memories, and a new language may find a way to emerge.

In the Gezi resistance, LGBTQ individuals had the same attitude as they have always had, appearing and resisting like they are used to doing. We were there, saying “What the hell is a prohibition, ayol!”

We were there with our own jargon, which soon became one of the most popular jargons and slogans of the Gezi resistance. However, this time, what has flourished in such a space is the mutual respect; a kind of “belated embrace.”

The so-called “sissy boys” who carried the wounded ones out of the clash zones, the previously slanged transwomen who supplied medicine and food to the barricades, and “fags” who apparently showed the courage of sitting in front of the police water cannon trucks like all those “tough guys,” together gave rise to a substantial crack in hate speech, and the homophobic and transphobic collective memory woven by it within and hopefully somewhere out of the space of the resistance.

Surely, such a crack that has opened up in the hegemonic discourse against LGBTQ people won’t put an end to hate speech and hate crimes in Turkey.

There’s a long way of struggle that lies in front of us. However, it has shed some light on the truth beyond its overwhelming darkness.

I want to finish with the words of Leonard Cohen:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That`s how the light gets in.